The Trump administration, escalating its campaign of imperialist violence in Venezuela, bombed military installations in the country and kidnapped President Maduro under the pretext of targeting drug cartels, but in reality having the oil reserves as the direct target of the mafia operations of US imperialism.

Trump had made this clear in statements to the media and in posts on social media. He had vowed that US military attacks on Venezuela would escalate until “all the oil, land and other assets that were previously stolen from us are returned to the United States of America.” Carrying out these threats, Washington has carried out airstrikes against Venezuelan targets in recent hours, culminating in the kidnapping of the country’s President.

The White House’s mafia-style operations make it clear that Washington’s goals include much more than Venezuela. They amount to an effort to recolonize Latin America as a whole and the abject subjugation of the entire region to U.S. profit interests, with threats to bomb Mexico, attacks on Colombian President Gustavo Petro, and the imposition of 50% tariffs on Brazil for supporting convicted coup plotter former President Jair Bolsonaro. Historically, Venezuela has played a huge role in the evolution of U.S. imperialist doctrine in the Western Hemisphere. This is partly due to its vast oil wealth, which at the height of Standard Oil’s (Rockefeller) dominance, accounted for fully half of the profits that US capitalists made from Latin America.

US interventionism in Venezuela, however, predates even the start of large-scale oil drilling by more than a decade, beginning with the so-called Venezuelan crisis of 1902-1903. At that time, a fleet of warships was deployed off the coast of Venezuela. Battleships bombarded ports, killing hundreds of civilians, and foreign troops seized control of customs. The armada was then sent by Germany, Britain, and Italy. The pretext was the refusal of the Venezuelan government, then led by President Cipriano Castro, to meet debt payments.

Castro came to power in 1899 to confront a “Liberation Revolution” (in today’s version “color revolution”) led by Venezuela’s richest man, Antonio Matos, and supported by foreign capital, particularly the American-owned New York and Bermudez Company, the German Great Venezuelan Railway, and the French Interoceanic Cable Company. After a painful civil war that devastated Venezuela’s economy and emptied its state coffers, Castro refused to comply with the demands of British imperialists, who had large outstanding loans, and German creditors (mostly Jewish), who had invested heavily in the country.

The European powers demanded immediate payment of outstanding debts and compensation for property destroyed in the civil war they had instigated. They were determined to impose their will through a naval blockade. Castro ignored the ultimatums, while appealing to popular nationalist sentiments that erupted in riots and looting of foreign businesses.

US President Theodore Roosevelt did not object in principle to the major capitalist powers using armed aggression to extract wealth from the oppressed country. He is reported to have told a German diplomat: “If any South American country treats any European country badly, let the European country beat it up.” He added, however, that “punishment should not take the form of territorial acquisition by any non-American power.”

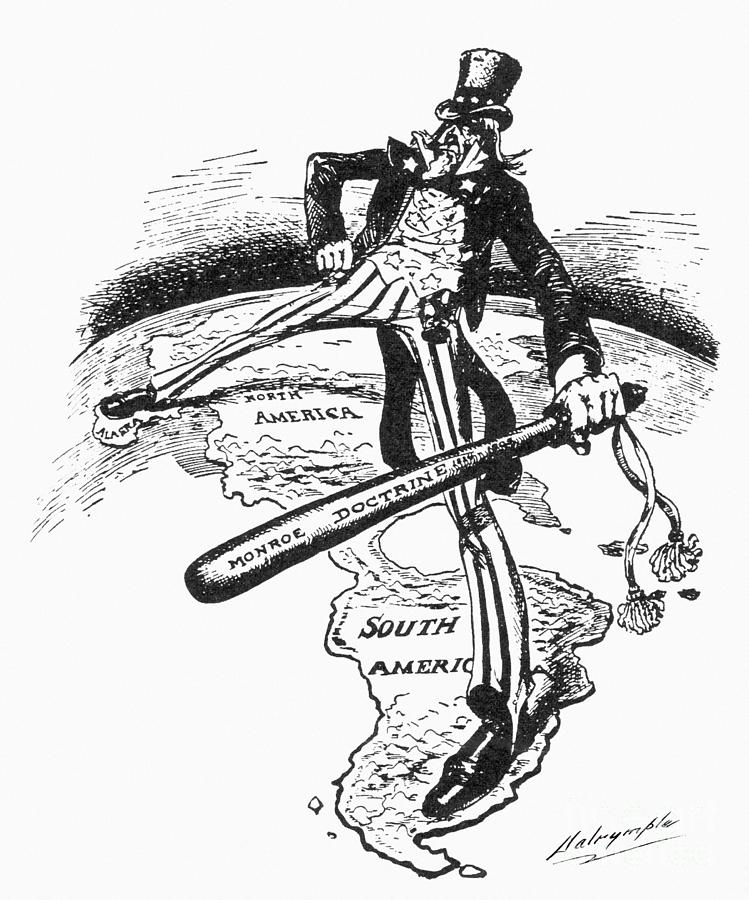

This warning was a reaffirmation of the Monroe Doctrine, a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy first articulated by President James Monroe, who in 1823 declared: “The American continents, in the free and independent condition which they have assumed and retain, must not henceforth be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European power.”

By the end of the 19th century, this anti-colonial and democratically inspired warning to the crowned heads of Europe had already undergone a solid transformation. It was invoked by the US government to justify the annexation of Texas as a slave state and the theft by war of more than half of Mexico’s territory in 1848. This process was rapidly accelerated by the Spanish-American War of 1898, the US seizure of Spanish colonial possessions, and the emergence of the US on the world stage as a major imperialist power, intent on seizing control of markets and sources of raw materials and cheap labor through military incursions.

In the crisis of 1902-1903, the Castro government in Venezuela appealed to Washington to mediate in the conflict over outstanding debts. Roosevelt accepted and called on the British and German governments to resign. While the British were tolerant, Kaiser Wilhelm II, who had overseen Germany’s rise as a military power with the largest army in the world and a navy second only to Britain’s, was determined to secure the “place in the sun” for German-Jewish capitalism.

Roosevelt feared that Germany would use the Venezuelan crisis to seize key naval bases controlling the Caribbean shipping lanes and, in particular, access to a planned strategic canal across the Central American isthmus connecting the Atlantic and Pacific. He issued an ultimatum to Germany to accept U.S. mediation and withdraw its warships. The U.S. president informed the German ambassador that Washington was assembling its own armada off Puerto Rico under the command of Admiral George Dewey, who had gained international fame for defeating the Spanish fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay in 1898, in the Philippines. Faced with the prospect of war with the United States under conditions in which it would be difficult to supply or reinforce its fleet, Germany withdrew.

Roosevelt made it clear that American imperialism had usurped for itself the exclusive right to exercise “international police power” in the Western Hemisphere. If Latin American countries were “beaten,” their ports bombed, their citizens massacred, and their customs houses seized, the United States would do the job, not its European rivals.

Roosevelt’s proclamation of this far-reaching follow-up to the Monroe Doctrine was quickly implemented through a wave of interventions, invasions, and occupations. This imperialist onslaught was succinctly summarized by Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler in 1935, who stated in a 1935 review of his career:

“I spent most of my time as a high-class muscle man for big business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer. a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenue. I helped rape half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped clean up Nicaragua for the Brown Brothers International Banking House in 1902-1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras right for American fruit companies in 1903. In China in 1927 I helped keep Standard Oil going. Looking back, I may have given Al Capone some advice.”

Venezuela was by no means immune to the mafia’s maelstrom. Washington helped engineer what would now be called a regime change operation in 1908, installing Castro’s vice president and former comrade-in-arms, Juan Vicente Gómez, in the presidential palace while Castro sought medical treatment in Europe. Gómez, who immediately called on Washington to send gunboats to “stabilize” the situation, would rule the country as dictator until his death in 1935. He also called Matos, the wealthy banker who led the so-called “Liberation Revolution” supported by foreign capital, back to Venezuela to take charge of its foreign relations.

Gómez’s dictatorship appealed to Washington and the American oil companies, which would emerge as the dominant power in Venezuela after the first well was drilled in 1912 in the Maracaibo Basin. Within a little more than a decade, Venezuela would become the world’s largest oil exporter and the second largest producer, behind only the United States.

Gómez unilaterally seized power, handing out concessions to foreign companies, including most notably the Rockefellers’ Standard Oil, giving them control over vast tracts of land. He quickly became the richest man in Venezuela, while leaving the lion’s share of the country’s wealth to Wall Street and the oil companies to plunder, and using a portion of his bribes to buy the loyalty of his supporters and the military.

Venezuela became even more strategically important to US imperialism and its profiteering interests after President Lázaro Cárdenas nationalized Mexico’s oil industry in 1938. With its oil reserves monopolized by American and Anglo-Dutch multinationals, Venezuela became vital for supplying the US military during World War II, as well as for fueling the postwar economic boom and the escalating Cold War.

During the 20th century, as CIA-backed military coups brought dictatorships to power in much of South America, the Monroe Doctrine underwent yet another revision, this time in the Kennan Doctrine, named after the American diplomat George F. Kennan who wrote the containment policy toward the Soviet Union. Applied to Latin America, this became the doctrine of “national security” in which any revolutionary threat from below was to be seen as a manifestation of Soviet expansionism and ruthlessly suppressed.

Under the presidency of nationalist Carlos Andrés Pérez, the Venezuelan government nationalized the oil industry in 1976 amid the sharp price increases that accompanied the energy crises of the period. Contrary to Trump’s claims that Venezuela was “stealing” oil and land from the United States, oil companies were compensated about $1 billion at the time. Moreover, neither the oil nor the land was ever owned by the United States, with Standard Oil and others plundering the resources through generous concessions granted by successive Venezuelan regimes.

Venezuela, however, remained completely dependent for income on a single commodity, oil, which it sold overwhelmingly to the United States, leaving it at the mercy of market fluctuations. Foreign oil companies continued their operations and made profits, while attempts to use import substitution to diversify the economy failed, leaving Venezuela dependent on imports for 80% of its food, as well as most of its industrial products.

The dominance of the economy by a single export sector (oil) led to the stagnation of other sectors, such as manufacturing and agriculture, leaving the country vulnerable to severe crises when export prices fell. This led to the escalation of social inequality and rampant corruption, while the country’s debts steadily increased. Returning to power for a second term, Carlos Andrés Pérez responded to the sharp drop in oil prices by opening the country’s oil fields to foreign exploitation and imposing a drastic “shock therapy” program dictated by the International Monetary Fund that included a 100% increase in fuel prices.

Continued unrest followed, punctuated by a failed coup attempt in 1992 led by a young officer, Hugo Chávez, who took office six years later in an election. His government used high oil prices to finance social programs that improved education and healthcare while alleviating poverty. These fairly modest reforms were followed by economic and political ties with Cuba, with Chavez condemning the US invasion of Afghanistan, leading to growing hostility from Washington.

This friction culminated in a US-backed coup in April 2002, which saw Chávez briefly deposed and imprisoned before mass protests forced his reinstatement. It is worth noting that the coup was led by María Corina Machado, who was recently awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her support of a US war of regime change in Venezuela.

In 2007, the Chávez government carried out another round of nationalizations, reversing the privatizations and handovers to US-based companies that had been carried out by Andrés Pérez. This measure was taken only after ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips refused to allow the government to take majority stakes in new concession agreements.

After Chavez’s death and his succession by Nicolas Maduro in 2013, the collapse of oil prices, exacerbated by punitive economic sanctions imposed by the Obama administration and intensified since then, led to a dramatic contraction of the Venezuelan economy, mass emigration abroad, and a sharp decline in living standards.

US intervention escalated, including through coups, assassination attempts, and even the landing of mercenaries on Venezuelan shores. The Trump administration sought to impose its own president, the unelected and largely unknown Juan Guaido, whose “interim government” failed to gain popular support.

With the deployment of a US fleet off the coast of Venezuela, the bombing of military targets and the kidnapping/kidnapping of President Maduro, we are witnessing the proclamation of two consequences of the Monroe Doctrine, 124 years apart, which seems to confirm this saying.

However, Theodore Roosevelt used the crisis of 1902 to modify the Monroe Doctrine in accordance with the predatory interests of American imperialism as a rising world power. Trump’s “consequence” is, however, the expression of the increasingly intractable crisis of that same power and the loss of global hegemony, which he is desperately trying to overcome through aggression.

China has already surpassed the US as South America’s top trading partner and is expected to surpass it across Latin America and the Caribbean by 2035. It is making large-scale infrastructure investments, from the new port in Chancay, Peru, to the creation of 5G networks, that the US is unable to match. Meanwhile, the European Union is also seeking its own access to the region’s strategically vital sources of raw materials.

In these circumstances, we recall that the National Security Strategy document issued by the White House on December 4, 2025, states:

“After years of neglect, the US will reaffirm and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American primacy in the Western Hemisphere and to protect our homeland and our access to key geographies throughout the region. We will deny non-hemispheric adversaries the ability to station forces or other threatening capabilities or to possess or control strategically vital assets in our hemisphere.

This “Trump Conclusion” to the Monroe Doctrine is a common sense and powerful restoration of American power and priorities, in line with American security interests.

The path charted by this new assertion of the Monroe Doctrine seems, at first glance, more delusional than “common sense.” It represents, more than any other historical juncture, the sure path to war. The goals articulated by the Trump administration cannot be achieved except through military conquest and direct military confrontation with China and Russia.

At the same time, the attempt to impose neocolonial ties on Latin America will inevitably provoke a gigantic explosion of confrontation throughout the Western Hemisphere.

The system of American imperialism is dragging humanity into the abyss of a global confrontation.